Research indicates that we are not simply born with good or bad attention and executive function. There is natural variation in attention profiles. For example children with ADHD and dyslexia have a distributed attention capacity and are poor in working memory and executive function. Some of us tend towards an open expansive awareness, and others naturally gravitate toward a more narrow focus. Both ways of being have their strengths, so it is not the case that we expect everyone must become someone who always has a narrow focus. It is not the point to become something different than what is your natural state, but to learn to use your attention ability. When we learn to direct our attention, those who are generally more expansive learn to narrow their focus when needed, and those who are by nature holding a more narrow focus learn to move into states of expansive awareness, when appropriate.

Building the attention networks and training those networks to function according to what the situation demands is a developmental process. This means, the development of these capacities requires time and an understanding of how these systems work and what they need to develop in a healthy way. Attention systems in the brain are developing and unfolding as the child matures, whether these systems are developing in a healthy way is what we must make our primary concern as educators.

Today schools are calling for more rigor and academics earlier and earlier. This focus on academics reduces the time to build the foundational systems of the brain. Lessons are focused on academic content from very early on. Without having built the basic foundation for attention, the demands of academic work puts a heavy burden on both the teachers and students. We are being asked to teach to a brain system that has not been developed yet.

I spent the early part of my career focused on understanding the cognitive capacities of attention and executive function. It was during the late 1990s, a time when we saw a great increase in diagnosis and treatment of ADHD. It was also the time of the growing understanding of the processes of neuroplasticity. What an amazing time to be in the field of neuroscience.

Being engulfed in this knowledge of neuroplasticity, I came to believe we could build attention systems and avoid the use of heavy-duty pharmaceuticals in our young children’s developing brains. I decided that the developmental changes necessary to build healthy attention system should be a part of how we teach in every school. Healthy attention and healthy brains should be a child’s birthright. Hence, my entry into the field of education came out of this deep desire to create curriculum that would build our children’s attention networks of the brain.

Building the attention networks and training those networks to function according to what the situation demands is a developmental process. This means, the development of these capacities requires time and an understanding of how these systems work and what they need to develop in a healthy way. Attention systems in the brain are developing and unfolding as the child matures, whether these systems are developing in a healthy way is what we must make our primary concern as educators.

Today schools are calling for more rigor and academics earlier and earlier. This focus on academics reduces the time to build the foundational systems of the brain. Lessons are focused on academic content from very early on. Without having built the basic foundation for attention, the demands of academic work puts a heavy burden on both the teachers and students. We are being asked to teach to a brain system that has not been developed yet.

I spent the early part of my career focused on understanding the cognitive capacities of attention and executive function. It was during the late 1990s, a time when we saw a great increase in diagnosis and treatment of ADHD. It was also the time of the growing understanding of the processes of neuroplasticity. What an amazing time to be in the field of neuroscience.

Being engulfed in this knowledge of neuroplasticity, I came to believe we could build attention systems and avoid the use of heavy-duty pharmaceuticals in our young children’s developing brains. I decided that the developmental changes necessary to build healthy attention system should be a part of how we teach in every school. Healthy attention and healthy brains should be a child’s birthright. Hence, my entry into the field of education came out of this deep desire to create curriculum that would build our children’s attention networks of the brain.

Patricia Goldman-Rakic is known best for her work studying the prefrontal cortex and specifically executive function. Executive function is one of the most well researched cognitive capacities and is the central neural system involved in what we commonly call attention. Attention is multi-faceted, but for our purposes in education we tend to consistently look at executive function as attention. Daniel Kahneman refers to tasks that require executive function as System 2 tasks. Schools today rely heavily on activities that use the frontal executor. What we know is that the frontal executor can experience fatigue. There is only so much that we can demand of this system before it poops out. To expect our students to learn primarily from this system is fighting an uphill battle. As they start to reach fatigue, we push harder, and this creates greater fatigue.

Michael Posner’s work on attention, showed that there are in fact multiple attention networks in the brain. Most people think only of the frontal lobe in attention processing, and indeed Posner identified the role of the frontal lobe in what he refers to as the anterior attention network, but he also identified an attention network in the posterior parietal cortex. Many of the activities in conceptual math engage this posterior system and bypass the frontal demands. Why this is important is that non-traditional learners, students with attention or other learning differences, have difficulty accessing the frontal executor. These students need to be taught differently.

Attention networks can also be viewed from their involvement of deeper structures in the brain, particularly, the role of the basal ganglia in directing intentional actions. Because this is a deeper structure, it develops earlier. It is a starting place for working on building attention.

Michael Posner’s work on attention, showed that there are in fact multiple attention networks in the brain. Most people think only of the frontal lobe in attention processing, and indeed Posner identified the role of the frontal lobe in what he refers to as the anterior attention network, but he also identified an attention network in the posterior parietal cortex. Many of the activities in conceptual math engage this posterior system and bypass the frontal demands. Why this is important is that non-traditional learners, students with attention or other learning differences, have difficulty accessing the frontal executor. These students need to be taught differently.

Attention networks can also be viewed from their involvement of deeper structures in the brain, particularly, the role of the basal ganglia in directing intentional actions. Because this is a deeper structure, it develops earlier. It is a starting place for working on building attention.

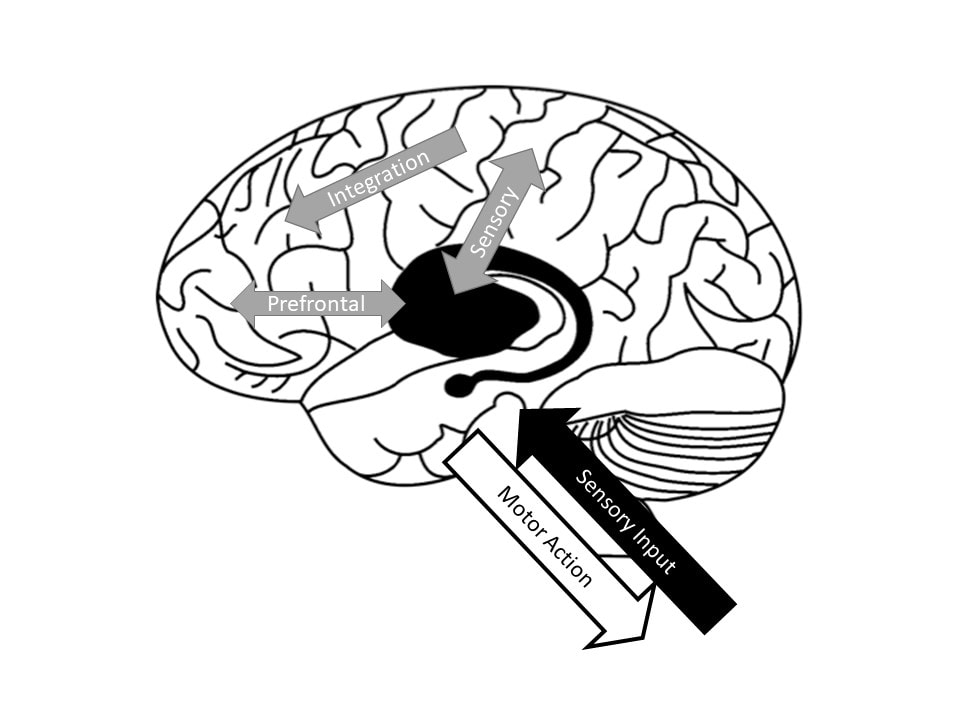

Figure Above. The region shown in black, underneath the cortex is the striatum, the central nucleus of the basal ganglia. Sensory information from the body comes in through the spinal cord, it flows through the thalamus (not shown) that sends inputs to the basal ganglia and the cortex. There is bi-directional connections with sensory/motor regions in the striatum. This information is integrated with information in the prefrontal cortex that then helps to direct intentional actions directed by the basal ganglia motor output streams.

For those interested in neuroanatomy, you might be curious about what is at the end of the long black tail of the striatum. The bulbous point at is the amygdala. How these two structures interact certainly show us how our emotions influence our drives, habits and learning.

There are bidirectional loops of information flowing between the basal ganglia and the frontal cortex. This is literally the foundation for our attention networks. Sensory information from the body comes up through the spinal cord, into the cortex and back down into the basal ganglia where it is used to direct our actions.

The visual information flowing through the “where pathway” in the parietal lobe, is combined with that of the sensory representation of the body. But the flow of information doesn’t stop there, it continues on to the frontal lobe, particularly, the prefrontal cortex and that information is fed at multiple stops into the basal ganglia.

If this frontal executor isn’t online helping to direct our actions, we tend to default to a reflexive way of responding. Because the actions of the basal ganglia are all subconscious, when it is running the show, we don’t have to think about what we are doing. With the basal ganglia in charge we are in automatic mode. When we see an object, we will reflexively pick it up and start to use it as it was designed, or sometimes otherwise. These types of automatic motor loops develop over time in the basal ganglia. Typically when the frontal lobe is well developed, it helps to inhibit those automatic responses and motor routines played out by the basal ganglia. However, as we know, the development of the frontal lobe, and prefrontal cortex, takes time.

The frontal cortex and basal ganglia receive lots and lots of dopamine. Most people know dopamine as the reward molecule. It is associated with most drugs that are addictive. It is also released naturally when we get a reward. People don’t know that it is critically important in intentional movement. It is interesting to note that the major drugs for ADHD all work through enhancing dopamine release.

I have a particular interest in drawing attention to what most teachers notice automatically, that our male students tend to show the most attention difficulties. All of the research on ADHD shows this pattern. Why do boys seem to have these difficulties? I believe it is because of the unique differences in the male and female brains, in particular in this dorsal/”where” stream and in the striatum nucleus. Giedd and colleagues examined the development of different brain regions in the male and female brain. He found that boys have a longer developmental period and thicker cortical mantle in the visual and parietal stream and the striatum nucleus (Lenroot et al. 2007). I believe this thicker mantle, with more neurons, requires more nurturing through experience to fully develop.

How do we develop this stream? This stream is critically linked to the somatosensory motor system. The somatosensory motor system, in order for it to develop, requires that we engage in movement in space, with attention and awareness. How sad is it that our boys who need to move and explore to develop that somatosensory motor network, are labeled as having attention deficits and are given powerful psychotropic medications.

These changes are developmental in nature, and it is important to note that the basal ganglia network as it is connected to the somatosensory system is one of the first to develop. All the developmental stage theories, such as those of Piaget, Erikson and even Freud, emphasize the importance of the somatosensory and motor systems early in development. The motor system, as it matures integrates information from the visual system and other sensory systems. It is in this place of integration that we develop spatial awareness first with our own body in space, and then in the capacity for abstract representations. It is from this point that we move all those representations into our prefrontal lobe to become places of planning, envisioning, and determining our actions.

So what have we done in our schools? We have removed many of the opportunities for students to move and move freely. I believe, there is no better way for the brain to truly unfold to its highest capacity than to allow for ample time for self-exploration.

As the brain develops, it seeks out those experiences it needs for the natural unfolding of cognitive capacities. The most important thing to understand about neuroplasticity, is that it is activity dependent. The systems cannot connect if the experiences are not provided. For example, think of language development. As the language centers develop, the child begins to babble, as the motor system develops, the child seeks out movement activities commensurate with the skill they are building. They need to have the experience for those networks to connect.

Although some are crying for more exercise, more recess, and more physical education, conceptual math provides another approach. The integration of movement into the curriculum not only helps to deepen the learning experiences of the children. Conceptual Math utilizes jumping, moving shapes, passing objects, physically creating shapes with the body, and a number of other games that can be adapted to fit within the classroom space. These sensory and motor activities are necessary for unfolding the full capacity of their brain and building the foundation for our attention and executive function.

The research around the importance of executive function in student performance is overwhelming. Test scores are tied to better executive function, and even IQ scores. So we know it is important. We also know that it is a capacity that can be built. There have been programs developed over the past 10 or 20 years that have focused on this goal. Many of them miss the point that to build a healthy attention system we should work from a developmental perspective. Many of the current programs teach tricks to organization. What a truly developmental approach requires is that we create opportunities for movement with attention and awareness to build the connections between the basal ganglia and the frontal cortex.

There are many other aspects of conceptual math that gently use the frontal executor. For example, the counting activities and mental math require holding information online and remembering it, hence using the frontal working memory system. But beyond this, the goal is to build the neural systems that develop before and provide the foundation for the prefrontal cortex. From the beginning, we want to work on building the foundation of our attention systems. We can do this through movement with attention and awareness.

There are bidirectional loops of information flowing between the basal ganglia and the frontal cortex. This is literally the foundation for our attention networks. Sensory information from the body comes up through the spinal cord, into the cortex and back down into the basal ganglia where it is used to direct our actions.

The visual information flowing through the “where pathway” in the parietal lobe, is combined with that of the sensory representation of the body. But the flow of information doesn’t stop there, it continues on to the frontal lobe, particularly, the prefrontal cortex and that information is fed at multiple stops into the basal ganglia.

If this frontal executor isn’t online helping to direct our actions, we tend to default to a reflexive way of responding. Because the actions of the basal ganglia are all subconscious, when it is running the show, we don’t have to think about what we are doing. With the basal ganglia in charge we are in automatic mode. When we see an object, we will reflexively pick it up and start to use it as it was designed, or sometimes otherwise. These types of automatic motor loops develop over time in the basal ganglia. Typically when the frontal lobe is well developed, it helps to inhibit those automatic responses and motor routines played out by the basal ganglia. However, as we know, the development of the frontal lobe, and prefrontal cortex, takes time.

The frontal cortex and basal ganglia receive lots and lots of dopamine. Most people know dopamine as the reward molecule. It is associated with most drugs that are addictive. It is also released naturally when we get a reward. People don’t know that it is critically important in intentional movement. It is interesting to note that the major drugs for ADHD all work through enhancing dopamine release.

I have a particular interest in drawing attention to what most teachers notice automatically, that our male students tend to show the most attention difficulties. All of the research on ADHD shows this pattern. Why do boys seem to have these difficulties? I believe it is because of the unique differences in the male and female brains, in particular in this dorsal/”where” stream and in the striatum nucleus. Giedd and colleagues examined the development of different brain regions in the male and female brain. He found that boys have a longer developmental period and thicker cortical mantle in the visual and parietal stream and the striatum nucleus (Lenroot et al. 2007). I believe this thicker mantle, with more neurons, requires more nurturing through experience to fully develop.

How do we develop this stream? This stream is critically linked to the somatosensory motor system. The somatosensory motor system, in order for it to develop, requires that we engage in movement in space, with attention and awareness. How sad is it that our boys who need to move and explore to develop that somatosensory motor network, are labeled as having attention deficits and are given powerful psychotropic medications.

These changes are developmental in nature, and it is important to note that the basal ganglia network as it is connected to the somatosensory system is one of the first to develop. All the developmental stage theories, such as those of Piaget, Erikson and even Freud, emphasize the importance of the somatosensory and motor systems early in development. The motor system, as it matures integrates information from the visual system and other sensory systems. It is in this place of integration that we develop spatial awareness first with our own body in space, and then in the capacity for abstract representations. It is from this point that we move all those representations into our prefrontal lobe to become places of planning, envisioning, and determining our actions.

So what have we done in our schools? We have removed many of the opportunities for students to move and move freely. I believe, there is no better way for the brain to truly unfold to its highest capacity than to allow for ample time for self-exploration.

As the brain develops, it seeks out those experiences it needs for the natural unfolding of cognitive capacities. The most important thing to understand about neuroplasticity, is that it is activity dependent. The systems cannot connect if the experiences are not provided. For example, think of language development. As the language centers develop, the child begins to babble, as the motor system develops, the child seeks out movement activities commensurate with the skill they are building. They need to have the experience for those networks to connect.

Although some are crying for more exercise, more recess, and more physical education, conceptual math provides another approach. The integration of movement into the curriculum not only helps to deepen the learning experiences of the children. Conceptual Math utilizes jumping, moving shapes, passing objects, physically creating shapes with the body, and a number of other games that can be adapted to fit within the classroom space. These sensory and motor activities are necessary for unfolding the full capacity of their brain and building the foundation for our attention and executive function.

The research around the importance of executive function in student performance is overwhelming. Test scores are tied to better executive function, and even IQ scores. So we know it is important. We also know that it is a capacity that can be built. There have been programs developed over the past 10 or 20 years that have focused on this goal. Many of them miss the point that to build a healthy attention system we should work from a developmental perspective. Many of the current programs teach tricks to organization. What a truly developmental approach requires is that we create opportunities for movement with attention and awareness to build the connections between the basal ganglia and the frontal cortex.

There are many other aspects of conceptual math that gently use the frontal executor. For example, the counting activities and mental math require holding information online and remembering it, hence using the frontal working memory system. But beyond this, the goal is to build the neural systems that develop before and provide the foundation for the prefrontal cortex. From the beginning, we want to work on building the foundation of our attention systems. We can do this through movement with attention and awareness.